Does Powell want an equity market decline?

It seems so. Former Fed chair Bernanke spent a decade delivering a policy of actively pursuing a “wealth effect” via quantitative easing (QE), hoping that stock market gains would unleash additional spending in the economy. It didn’t really work, only serving to exacerbate the wealth divide. It took the government’s budget blowout during the pandemic to produce the real spending impulse across broad swathes of society. That spending has contributed to the inflation that threatens disaster at the polls for the Democratic Party in November.

90% of voters don’t own enough equities to care about the reverse wealth effect of falling markets. But they will vote out the incumbent party if gasoline and other psychologically impactful prices don’t decrease. The Fed is under intense pressure to assist in reining in headline inflation. To that effect, strange as it may sound, could it be that Powell actively wants to reduce (gradually, not suddenly) the froth in both the equity and real estate markets? Yes. The Fed is in a hawkish mode for the first time in fifteen years.

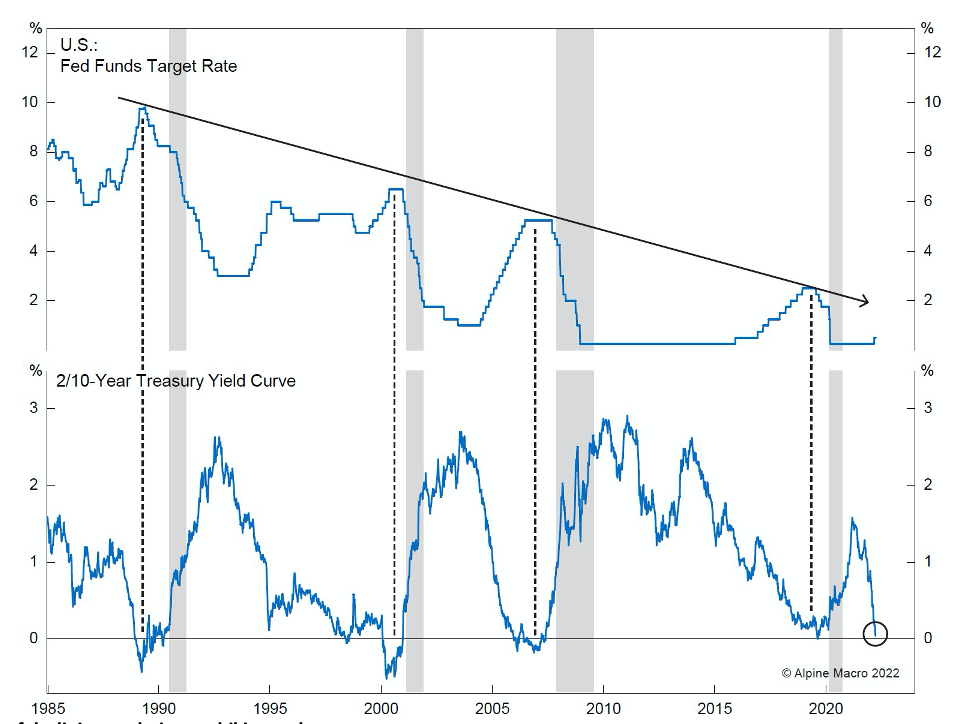

We are struggling to reconcile how the Fed will raise rates rapidly this year to an expected terminal rate of 3% in 2023 while also accelerating its balance sheet reduction under quantitative tightening (QT) and managing a soft landing for the broader economy. Today’s economy looks nothing like it did in the 1970s – we currently have a debt load that is 4x as large, poor long-term demographics, and much lower productivity. In every economic cycle over the past thirty years, R* has declined. R*, also known as the neutral interest rate, is a fancy economic concept that, in layman’s terms, represents how far the Fed can raise interest rates before something in the economy “breaks.” The chart on the next page shows these “break” points, which are denoted as recessions in the gray shaded areas.

Forty years of declining peaks in rate hiking cycles

Source: Alpine Macro

In a heavily financialized economy like the U.S., what breaks at the end of these rate hiking cycles is usually equity or real estate prices. Recall that as recently as Q4 2018, the stock market was in freefall, crashing 20%, tipped over by the Fed having raised rates to 2.5%. A few panicked phone calls by then-Treasury secretary Mnuchin and Fed Chairman Powell’s famous ‘pivot’ were required to restore confidence.

So how can the Fed raise rates as aggressively as they are posturing to do right now? They probably can’t, and they know that trouble will ensue somewhere in the 1-1.5% range. This is because Powell’s job as Fed chair is essentially political. And for now, as smart and savvy political operators, they are singing a tune that is in harmony with the party’s desires in power.

Correlations keep breaking down

Correlations continue to break down, as markets are shifting in recent months and quarters relative to the regimes that had prevailed for the previous thirty years. From watching market relationships in Q1 2022, we note:

- The consensus narrative in the financial community is that tech stocks are “long duration” assets with steady cash flows, and thus as long-end rates move, higher-tech stocks should suffer. But the Nasdaq has rallied in recent weeks as 10- and 30-year yields have skyrocketed. So, could that mean that a reversal (long-end yields moving lower) could also go with falling tech stocks? Sure, and that happened during the dot-com bust twenty years ago.

- The yen is no longer the ‘yen’ of 1990-2018. It seems to have completely lost its risk-off characteristics. Although the Bank of Japan has been dovish, the yen is still quite cheap on a PPP basis. Its behavior during the next consistent sell-off in equities will cement our view on how we should think about trading the yen in the years ahead. Could it consistently depreciate despite being the cheapest developed currency against the dollar?

- On a related note, the holy trinity bundle of “risk-off assets” – gold, Treasury bonds, and the yen – no longer trades in sync. The strength order used to be yen, bonds, and gold. Now it’s gold, bonds, yen. So gold is going its own way regardless of what the dollar does – that seems to comport with our thesis that gold is the last man standing when a monetary system comes to its denouement.

We expect that the correlations that all financial professionals have witnessed throughout their careers will continue to decay and blow apart. As a result, there will be tremendous opportunities ahead and risks in relying on traditional measures of relative value or relationships.

Commentary by AG Capital Management Partners, LP

Trading futures involves substantial risk of loss and is not suitable for all investors. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

Photo by Federal Reserve on Wikipedia