With the crude oil markets now trading well below where it was before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, observers may be forgiven for thinking that the consumer has won, meaning the producer has lost. Higher pump prices and the consumer’s weaker purchasing power certainly held back demand growth to only +1.85 million barrels per day (mln bbls/d) in 2022. Yet, by any measure, that’s still a very impressive yearly growth rate.

It should not be forgotten that the very firm hand of the state was visible in 2022. In response to the invasion, Western governments flooded markets with over one mln bbls/d of oil from its strategic stockpiles. At the same time, the largest producers of OPEC+ were adding back supply to restore their production rates to pre-pandemic levels.

Herein lies the catch: the supply side events that occurred last year cannot re-occur this year. China is reopening. COVID-19 is becoming only a memory. Governments may turn net buyers of oil in 2023 rather than sellers. Sanctions on Russian oil by the G7 and the EU – the most punitive round yet – will only take effect in 2023. OPEC+ has tested the upper boundaries of its supply capacity. As a result, the world’s consumers are at risk of believing 2022 was a normal year for the oil market.

What happened in 2022…

While the pace of oil demand slowed in 2022, it is still growing. The consumer’s purchasing power has been clipped courtesy of a strong US dollar, higher interest rates, and a higher price at the pump. Those effects may linger through 2023, but one material change is the emergence of the world’s second-largest economy, China, from economic lockdown. COVID lockdowns have always weighed heaviest on mobility and, therefore, oil demand. That is all set to change as China’s zero covid policy is abandoned and suppressed demand will be released.

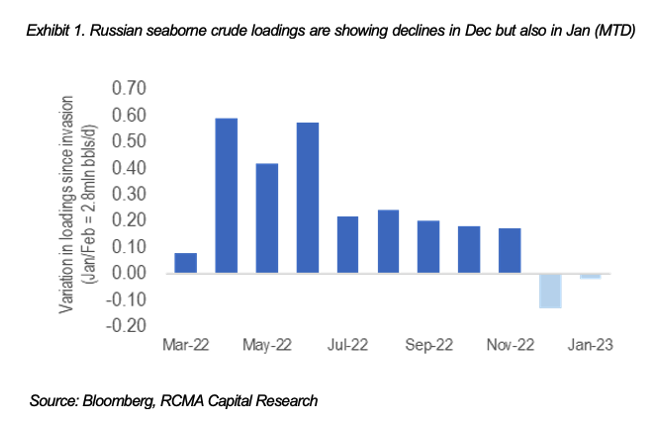

So far, the impact of western sanctions on the Russian oil supply has been limited. Yet, the most impactful sanctions to date – Europe’s embargo on Russian crude oil imports combined with the G7’s price cap – is only one month old. More sanctions are coming: the European embargo on refined Russian oil products will start in February. Russia is already working hard to place its unwanted crude oil into Asia. However, finding a willing home for its refined products, especially diesel, will prove a much harder task. This may force its refineries to curb crude runs, meaning upstream production will inevitably be shut in.

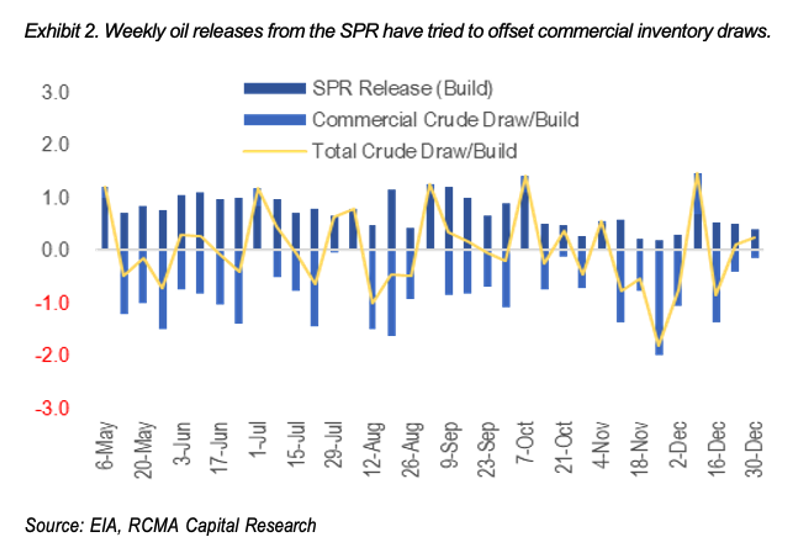

Governments also set new supply records in 2022. The coordinated release of emergency stockpiles in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine will be tough to repeat this year. The US administration quickly released 180mln bbls of crude oil from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). Under the guidance of the International Energy Agency (IEA), the rest of the world’s largest economies released an additional +90mln bbls of crude oil and products. This release was supposed to offset any lost supply. But Russian supply did not materially fall, yet the emergency stock releases – amounting to 1mln bbls/d of supply between April and December – kept coming. If pushed, the IEA could engineer another sizeable release in 2023, but the US would struggle to keep up the same pace. So instead, 2023 may be the year the US SPR turns into a net buyer of oil as what it has released must be eventually replenished at some time in the future.

Last year was also a year when OPEC+ took production to its limit. Many small and mid-sized members struggled to get close to their allocated quotas. Russian production was obviously constrained. Saudi throttled production up to 11.0mln bbls/ d and kept it there while the UAE and Kuwait followed. Never comfortable with this rate– Saudi was drawing heavily from its spare production capacity – those production plans changed. By October, led again by Saudi, OPEC+ reversed course and instituted a cut. Even after, overall OPEC+ production should still be considered high. After all, that growth is concentrated in a small band of Gulf producers. A lot could go wrong in 2023.

…cannot be repeated in 2023.

The combination of all the above turned a projected deficit into an actual surplus for global oil inventories over the latter part of 2022. The front loading of Russian oil imports into Europe and elsewhere ahead of sanctions and a very mild winter has certainly shielded the consumer from what could have been. But complacency may be setting in. The winter is not yet over, and a false sense of security of supply may be developing. This year, 2023, will be anything but normal.

Photo by Pawel Czerwinski on Unsplash