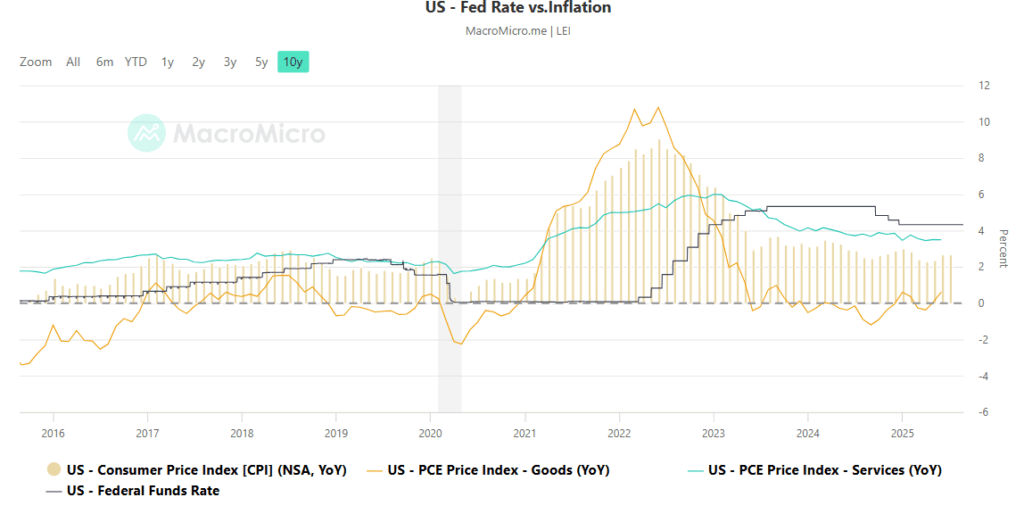

After months of telling the public that “Inflation is transitory,” the Fed finally admitted that it kept policy loose for too long in 2021. Months of rate hikes followed in 2022, dragging the stock market down as assets repriced. Now, the rates in the United States outpace those of major economic zones across the world. The result? Higher mortgage rates, growing interest on our national debt, and homeowners unwilling to sell to protect their 3% loan note. At the famous Jackson Hole conference last week, Powell confirmed that they might cut soon. Will it be soon enough?

The Dual Mandate

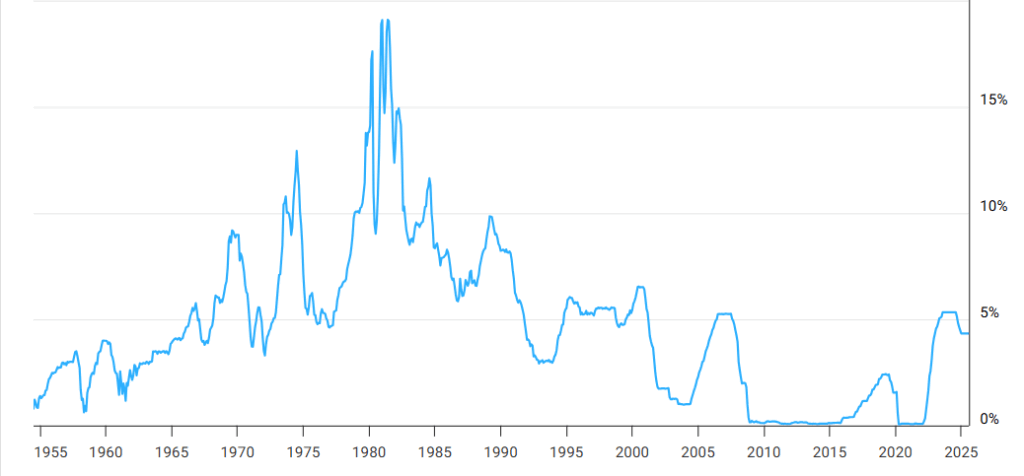

It is widely accepted that the dual mandate of the US Federal Reserve is to provide price stability and maximum employment. Resolution 133, adopted by Congress in 1975, instructs the Fed to do just that while maintaining moderate long-term interest rates. This resolution became official in 1977 with the passing of the Federal Reserve Act. Just three short years later, Paul Volcker, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, pushed rates above 15% to fight inflation, seemingly ignoring the employment mandate. He believed that the lack of price stability led to job losses and that preserving the value of the dollar provided the best chance for future jobs. When his philosophy yielded positive results on both fronts, talk of the “dual mandate” faded until 2010. That subsequent period, with rates below 1% lasted from the Financial Crisis of 2008 until 2017. COVID ushered in yet another period of low rates before the Fed began its current campaign.

Employment

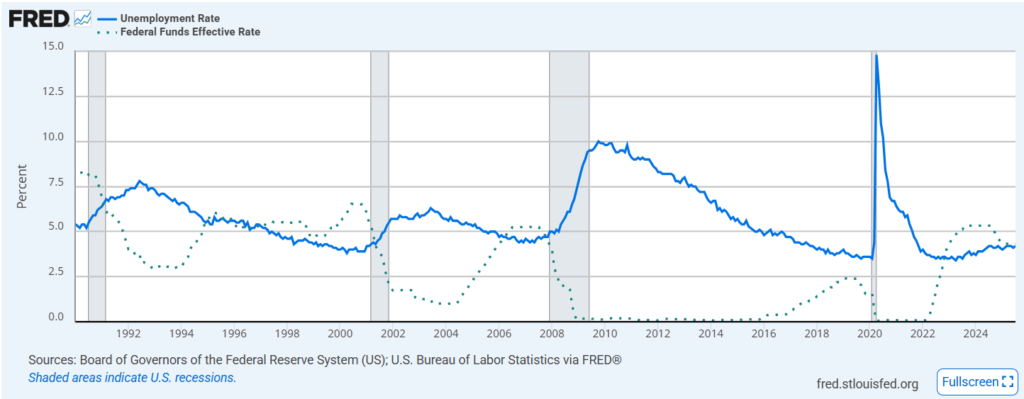

On the first measure, the US economy is at full employment. This is not defined at zero, as some rotation in jobs is needed. Without people to fill new roles, companies would be in a bind, and growth would stall throughout the economy. Wages would skyrocket to induce movement across companies. Often, the figure cited to denote full employment is 5%. We last crossed this mark in August 2021 and have kept below that level since then. Currently, we stand at 4.2%. By this measure, rates remain in good territory.

Inflation

Despite a drop from the highs of 2022, inflation is still running at a 2.7% rate. This is above the Fed target of 2% but dropping from highs of over 9%. The preceding period, from 2019 to early 2021, saw prices running below this long-term average. Some economists attribute this to the “Amazon Effect,” which helped price transparency and increased competition, putting many local shops out of business. Powell indicated at the time that he would be satisfied to let inflation run a bit hotter to catch up to the 2% average goal. This partially explains their failure to act until the consumer price index neared its peak in the summer of 2022.

Tariffs: Near-Term Effects

It remains unseen how tariffs will impact the current trend. Evidence thus far shows a muted response. Using GDP numbers, we can see that many importers front-ran the imposition of the additional fees. This led to a decrease in GDP numbers in Q4 2024 as goods shipped into the country subtract from GDP. These numbers have normalized recently and continue to show a growing economy. Exporters seem to be eating much of the new fees for now. The Federal Reserve of New York found that 62% of the fees were being passed on, with countries including China absorbing even more. The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) calculated that foreign profit margins went down from 12% to 7% on average, confirming this trend. When companies need to re-supply their inventory, it is possible the impact will grow, but so far, the response is manageable.

The Track Record

The embarrassment of the “transitory inflation” comment lingers for the Fed. Rather than being credited for managing a soft landing following the COVID lockdowns, the spike in prices to 30-year highs is likely what the Powell years will be remembered for. One could argue that policy choices from Congress forced their hand and left them in a no-win situation, but the result is the same. They were too late to tighten. This follows the mortgage crisis in 2008, which caused a worldwide meltdown of financial systems. Given that background, they might be loath to ease too soon and see inflation re-ignite.

The Outlook / Policy Dilemma

The lagging effects of policy changes make it difficult to get the timing exactly right. If the economy is slowing and they wait until a recession, it will be too late. European central bankers and the Bank of Canada began their rate cuts in 2024 as soon as signs of easing occurred. Exposure to US tariffs furthered this decision based on the fear that it could materially weaken their economies. It appears to be doing just that, with the Eurozone limping along at a 0.4% annualized rate and Canada experiencing stagflation levels of 0% growth. The revised US GDP number released on August 28, 2025, shows even better expansion than originally reported, further widening the growth gap between the countries. This puts the Fed in a tough spot.

Trade-Offs

Cutting rates would put them in line with other central banks, while leaving them elevated could lead to an excessively strong dollar, which would hurt exports. It would, however, preserve the buying power of the American consumer and help offset tariff pain. While the Fed maintains that they are apolitical, it clearly wants to keep its position of power. Pressure from Trump, who will pick the next Chairman, to reduce rates is growing. Perhaps he is tracking loan delinquency numbers, which show a clear trend higher. This is especially true for younger borrowers who thought their student loan debt might be erased and now need to make payments again. Credit card debt is also increasing, a clear sign of stress in the economy.

Conclusion

Jerome Powell indicated that at the next Fed meeting, they will likely vote for a modest reduction in rates. This would reduce political pressure, help the debt market, and make housing more attainable. Banks will likely benefit from customer refinancing and new loans. This would put the United States on a similar path to other countries. Proceeding slowly will give them maneuverability if things go south quickly for larger cuts. If, however, inflation comes back or another debt crisis emerges, raising interest rates soon after cutting them will affect confidence in their decision-making yet again. A costly mistake for the most important voice in finance.

Photo by Fineas Anton on Unsplash