Identifying weakness in markets can be a difficult task. Metrics like gross domestic product (GDP), equity market gains, and unemployment paint in broad strokes. Lenders often try to identify risk at a granular level. This might include tracking payments arriving late, higher credit card balances, increases in line of credit usage, or non-payment of insurance for loan collateral. All provide insight into borrowers struggling to keep up. If they fall behind completely, most will just stop paying and hide from their collectors. We saw how this can end in the 2008 mortgage crisis. Could autos be the first domino to fall this time?

Why autos matter (but get ignored)

Headlines typically focus on mortgage and student loan programs while ignoring vehicle lending. For most households, the second most valuable thing they own is their car or truck. In fact, the amount owed in this market is larger than student debt (for now), but unlike that sector, collateral backs these loans. Price increases throughout the pandemic and before drove average car payments to all-time highs. This makes sense with a 50% price increase since 2015 alongside lengthening loan terms, higher insurance rates, and exploding repair costs. These payments remove funds that could be spent elsewhere, forcing a reallocation of budget dollars for everyday living.

Insurance lapses: the early tell

Auto lending is a significant part of many financial institutions’ portfolios. These players include large lenders like Capital One and Ally Financial, community banks that support small-town business activity, credit unions, and, lastly, finance companies geared towards subprime borrowers. Money is disbursed through both direct and indirect lending. One typically obtains an indirect loan at the auto dealership, where they input your information and place you with a bank willing to offer the best rate. A direct loan is often originated where you hold your other accounts. Default rates on direct loans are typically lower because borrowers have a relationship with the lender and, in many small towns, even know the person who granted them the loan.

Insurance is required to protect their collateral as part of the customer agreement. Policies list the lender as the lienholder for the vehicle. This means that claim payments, particularly for a total loss or stolen car, go directly to the insurance company to satisfy outstanding debt before any amount is paid to the borrower. 10% of the loans at an average financial institution will be uninsured at any given time. For a $1.66 trillion industry, this means $166 billion is not covered. Since people need a car to get to work, they will often stop paying insurance first when they cannot keep up, and then the car payment itself. Various companies actively track this insurance to ensure financial institutions know their exposure and to see who might go into default so they can plan accordingly. Many will purchase insurance on their behalf for the amount owed and add it to their loan balance. These rates can be unattractive, to put it mildly.

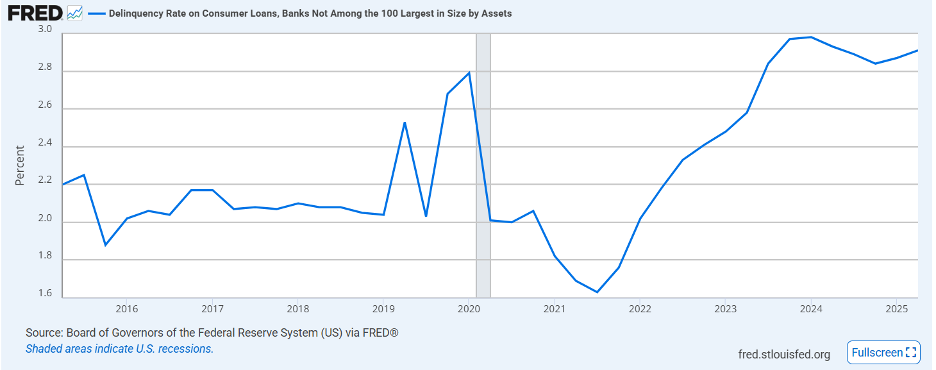

Delinquencies: what’s publicly reported

Banks and credit unions track how many late customers they have by grouping them into buckets: under 30 days, 30-90, and then 90 or more. Their goal is to work with people as quickly as possible to get them current and avoid repossession. It is here that public reporting begins, and the data does not look promising. The New York Fed shows 90-day delinquency for 5% of borrowers. This is nearing the 2010 peak of 5.3% and a 25% increase from this time last year. Younger (18-28 years old) and subprime borrowers show the most weakness across categories. Delinquency on autos for lower credit customers is at its highest rate ever recorded. Those with these scores often go to finance companies and cycle through cars and refinancing quickly. High interest rates hit them particularly hard as their normal rates often reach 20% or higher to offset the risk of non-payment. The resumption of student loan repayment seems to be putting them further into an economic hole. A reduction in interest rates seems to be needed by these groups as soon as possible, or else they face the next step, repossession.

Repossessions: the endgame

Lenders do not want their cars back, but they are left with few options for non-payment. Banks repossessed the most vehicles in 2024 since the financial crisis in 2009, as 1.73 million vehicles came back to the lienholder. Many of these come back damaged or vandalized, forcing them to file claims or sell them at steep discounts. Wholesale auction houses like Manheim benefit as thousands of cars need to be liquidated. 2025 is on pace for even greater volume. Much like the mortgage crisis, when bank-owned houses hit the market, this will drag down the value of all cars. Large financial institutions might have hundreds of thousands of loans at any given time. Losses will not be apparent at first, but as the collateral declines in value and repossessions increase, write-offs will come as well. Indirect loans will lose first, and then direct. This will come on top of commercial real estate and credit card trouble that is already on the horizon.

Summary

It is often said that the Fed is too late. Younger borrowers might already be too buried to recover. Poor decisions made with the belief that student loans might be cancelled will come with a price. This will affect everyone as assets get written down and used cars flood the market. Lower rates might ease this burden to avoid a crisis, but current data show a troubling pattern. Perhaps these losses will serve as an early warning sign and yet another reminder that buying high is usually not the best strategy.

Illustration created by ChatGPT (OpenAI / DALL·E)