Disclaimer: While investment in managed futures can help enhance returns and reduce risk, it can also do just the opposite and, in fact, result in further losses in a portfolio. In addition, studies conducted on managed futures as a whole may not be indicative of the performance of any individual CTA. The results of studies conducted in the past may not be indicative of current time periods.

AG Capital is a global macro investment firm, trading futures across currencies, commodities, equity indices, and interest rates. The firm follows a 100% discretionary approach, relying on fundamental analysis to choose long and short themes, with technical analysis informing the timing of entries and exits. Below is a sample piece showing how they see trading. This example sets up a trade viewed through the lens of a global macro firm.

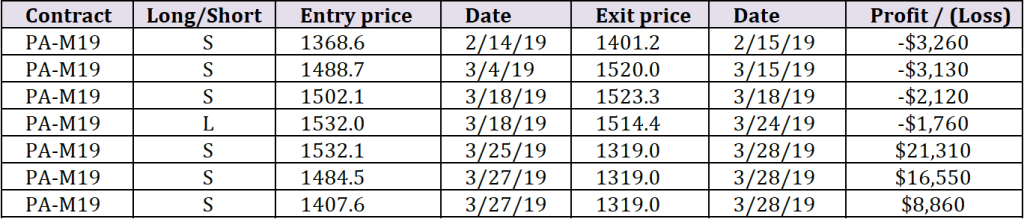

Our internal trade blotter from Q1 shows the following trades, all for palladium (June 2019 expiration), with the data normalized such that each entry in the table is for a single contract:

We’ve often stated that we manage our strategy with a primarily fundamental bent, so what is going on with the flip flop in the middle of the table, where we went from trying to short the market to buying it and then back to shorting it? What kind of schizophrenic behavior is this?

And didn’t we make good money on the long side of the palladium market last year and write about why it was in a bull market? So, how could we possibly look to go short so soon after making a bullish argument?

We’ll examine all the above in this letter, then close with some views on the divergences we are witnessing in the equity and bond markets.

Always hold both the bull and the bear case loosely, and manage the risk and the position

Our trading of palladium offers a nice window into our mindset as classic macro traders. But first, we need to define terms. We view most modern macro investing as being predominately quantitative or algorithmic in nature, with 40-100 positions (small bets) spread across countless markets, where each individual position is not watched too carefully. In contrast, we view classic macro as having a small number of positions (e.g., 3-5), each observed and either sold upon showing a loss or held and added to with conviction when showing a profit.

We believe that our style of classic macro trading involves understanding both the bull case and the bear case for each market that we follow and then mentally adjusting the conviction that we have in either the long or the short side as we watch price action play out. A criticism of this approach may be that it seems like it only relies on technical analysis in practice, but that is not correct – there is no way to hold a position with conviction if you do not understand the fundamentals. Let’s apply our analytical framework to our recent palladium trades and show you how we ended up trading it successfully.

The bull case: the bullish case for palladium relies upon the fact that auto industry demand shifted strongly away from diesel engines after the 2015 Volkswagen emissions scandal that tainted demand for the predominantly platinum-coated catalytic converters that diesel engines rely upon. Instead, demand for palladium skyrocketed, as it is the primary scrubbing metal that goes into gasoline-powered catalytic converters.

On the supply side, palladium is sourced as a by-product of other metals, from very few sources, primarily in Russia and South Africa. Rumors of Russian inventories being hoarded added further fuel to the bullish case, opening realistic targets of above $2,000 per ounce were a true shortage to develop.

Finally, it’s important to note that the auto industry has historically been able to re-tool its production lines from platinum to palladium and vice-versa. However, this is no easy feat and can require a couple of years of lead time. As such, the price has an “inelastic” response to changes in both demand and supply (couldn’t resist the urge to use some economics jargon from our Econ 101 class in college).

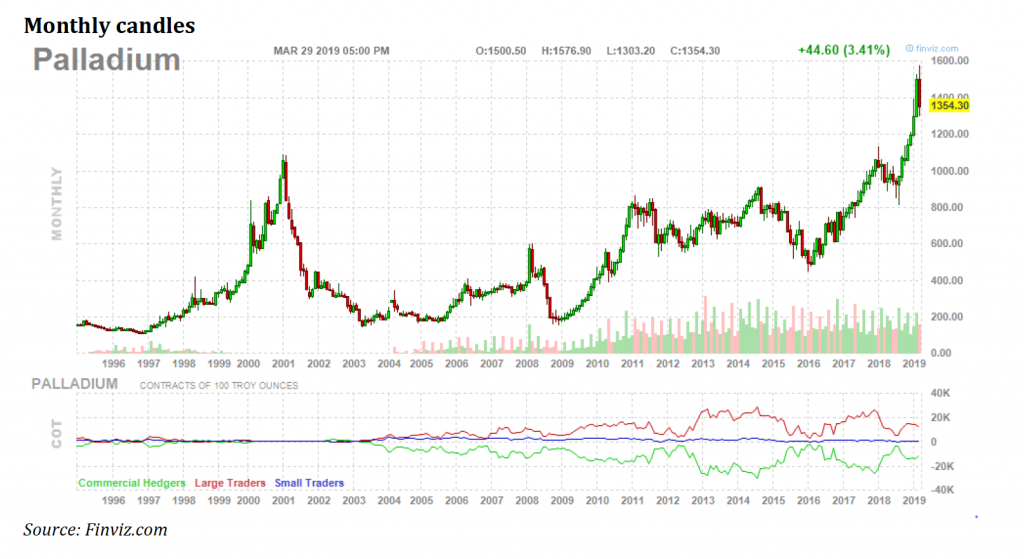

The bull case dominated and drove this market from mid-August 2018 until mid-March 2019, as seen in the daily candle chart above. This occurred despite data that showed auto demand falling globally, especially in China – that’s how you knew this was a very tight market.

The bear case: the bear case is simple. Every time any commodity market goes parabolic, there is a decent chance that prices have overshot, and it’s a matter of time before they come down to earth. This could be due to speculators adding additional longs simply

because the price is rising, or because the marginal physical buyer panics close to the top and attempts to add excess inventories for safety’s sake, further tightening the market. Or it could be due to a true corner (e.g., the Hunt brothers with silver in 1980, or the rumors that Russian palladium producers planned to sit on their inventories in 2019). Regardless, once it becomes clear to the market that we are not about to run out of the commodity (and we never run out of anything, let’s be honest; remember “peak oil”?), the market comes down hard, as the marginal price that clears the market is always far below the all-time high.

The bear base dominated during the past couple of weeks. It can be seen in the huge monthly red candle at the end of the chart below and in several other cases, such as the early 2000s, 2008, and 2011.

Let’s tie this back to our trading. We made good money on the long side late last year, effectively riding the bull case, but the entire time we kept the bear case tucked away mentally, knowing that we may need to dust it off soon. Come 2019, we primarily traded with the bear case, getting stopped out for small losses our first three tries, as can be seen from the table on page 1.

We then switched to a long position in palladium on March 18, 2019, the very same day that we were stopped out of our third short palladium attempt. What to the casual observer would appear to be inconsistent behavior is a tactic that lies at the heart of classical macro trading: when the market appears to disagree with your current position, instead of just taking the trade off, it is often more rewarding to endorse the opposite side of the trade. In other words, by flipping from the bear case to the bull case, we were mentally able to shift from our concern that palladium was in a bubble to instantaneously endorsing the notion that supply constraints would be able to send the market another major leg higher toward the $1,800 – $2,000 zone.

Why did we quickly switch back to the short side a few days later? Well, the market’s behavior over March 22-26 showed the classic signs of instability that mark a top – after breaking out to an all-time high the market reversed hard on March 22 and closed a few days later inside of the congestion region that it had built up from late February into early March. This appeared bearish to us, and we re-established our short position. From here, it was clear that the entire bull market advance from August 2018 was at risk, and as the market collapsed, we added to our position twice before closing the trade close to our short-side price target of $1,300.

As an aside, the fact that the trade took only a few days to move in our favor and get to our target is irrelevant; we anticipated it would take 1-2 months to get to $1,300 and were as surprised as anyone that it only took two days. However, a quick glance at the monthly candle chart above should quell any notion that this quick collapse was some sort of black swan event, as this market has on multiple occasions over the past two decades had similar sharp breaks to the downside.

A final comment on sentiment. Careful readers of our letters will note that we often examine fundamentals, technicals, and sentiment. Sentiment refers to the prevailing view endorsed by the majority of speculators/investors in the market and is used as a contrarian indicator. For example, if everyone and their mother is bullish crude oil (based on whatever narrative is being spun), you may want to look to take the other side of the trade and go short crude.

In the case of palladium, however, sentiment didn’t really help much. As can be seen from the monthly chart above, speculators, as defined by the red line at the bottom of the chart, never built up the massive position they had during prior peaks, and hence anyone using sentiment data as expressed by the CoT (Commitment of Traders) would have been caught off guard by the sharp move down in late March. The CoT data in this chart is not being expressed as a percentage of open interest so it isn’t the best way to view it, but it tells the same story as when you normalize by open interest. Bottom line: sentiment doesn’t always work; always take it with a big grain of salt.

To summarize the trade: palladium over the past few months has been a great example of an intermediate-term trading market for us, one where we hold both the bull and bear cases lightly until one side properly crystallizes for us, whereupon we pounce aggressively. There is always an underlying method to the madness of classic macro trading.

AG Capital is a fundamental, long/short macro investment firm, trading across currencies, commodities, interest rates, and equity futures.

The firm follows a fundamentally-oriented, discretionary long/short macro investing. We look for opportunities where imbalance between supply, demand, and inventories (where applicable) may lead to a large price move. Position hold times vary from 1 month to years; no day-trading, no algorithmic trading. Fundamental analysis is used to determine directional exposure, both long and short. Technical analysis is used to determine trade timing: enter and exit positions where extreme asymmetry exists from a risk/reward standpoint.