Archives

Mistakes Will Be Made – Just Don’t Make Any on Purpose

Mistakes were made. Mistakes will be made. Sorry, I made a mistake. Many think that an apology for mistakes is all forgiving. But the definition or type of mistake makes all the difference. Don’t make them on purpose.

Spend Your Time On “What Is”, Not “What If”

Spend your time on “what is”, not “what if”. I picked up the phrase from The 10 Pillars of Wealth by Alex Becker. It seems apt given many recent discussions on the global economic environment. I am a strong believer in scenario analysis and have talked about scenarios as good tools even for trend-followers to assess potential risks, yet there is a hidden or implicit assumption that is more important for any financial discussion – what is the current environment.

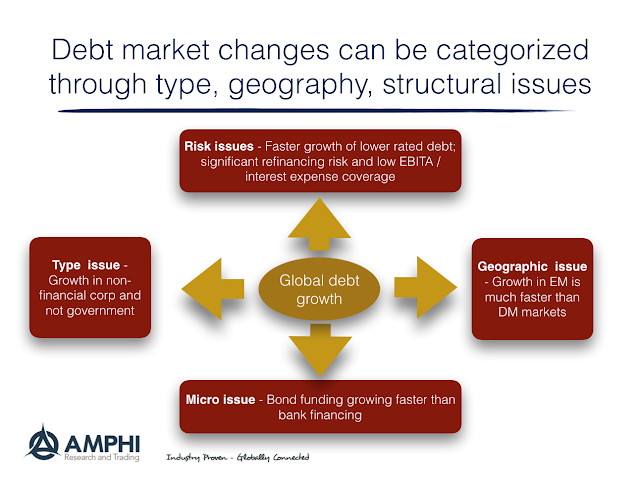

Debt – “If Something Cannot Go on Forever, It Will Stop” – The Problem Is Not If But, Figuring Out When

The McKinsey Global Institute published a new report, Rising Corporate Debt: Peril or Promise?, that is good reading for anyone focused on global debt issues. The charts and tables provide a wealth of data.

Keynes on Money – Do Not Hold Any as a Store of Value

“…for it is a recognized characteristics of money as a store of wealth that it is barren; whereas practically every other form of storing wealth yields some interest or profit. Why should anyone outside a lunatic asylum wish to use money as a store of wealth.

Because, partly on reasonable and partly on instinctive grounds, our desire to hold money as a store of wealth is a barometer of the degree of our distrust of our own calculation and conventions concerning the future.”

-Keynes

Focus on the Dislocations – These are the Places of Market Opportunity this Week

There are some recurring themes this week in our highlighted charts, debt and leverage will overhang any global economic discussion; however, we see some interesting dislocations that can offer global macro opportunities:

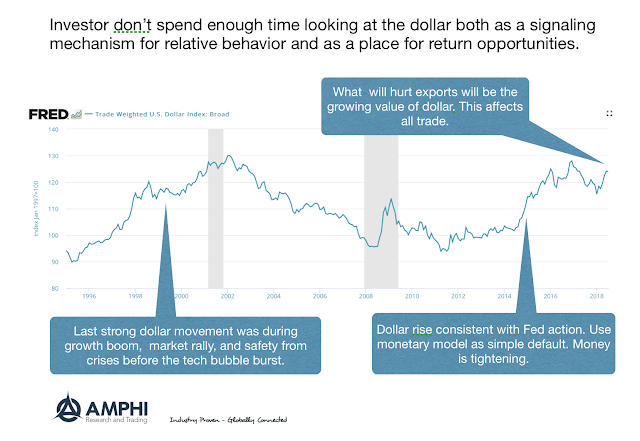

The Dollar is Sending Signals if You Care to Listen

I am concerned about tariffs. They are strong effects on importers and exporters in industries affected by tariffs and we don’t really know how tariffs will impact the supply chain and logistics for many companies. Nevertheless, the strong dollar will have a bigger impact on US exporters across the board.

How to Build Effective Economic Models – Translate to a Narrative and have Examples

a good mathematical theorem dealing with economic hypotheses was very unlikely to be good economics; and I went more and more on the rules

The Importance of Precision in Language: Lessons from Sherman Kent

I have written about Sherman Kent for years as someone who grappled with uncertainty and the language we use to discuss it. There is imprecision in the words we use such a “likely” and “probable”. Sherman Kent was a professor at Yale University who was called in to co-head the CIA’s National Office of Estimates and improve their forecasting skill. Getting the chance of a bad event wrong has real effects. During his tenure, Kent wrote an important piece on the use of ambiguous words to describe our probable estimates. He worked to end squishy vague language that provided political cover for assessment authors.

The Relationship between Financial and Real Assets is at Extremes – It Can Be Exploited

Correlation is not causality. Blending two variables on the same graph does not make a relationship, but there is a core link with the relationship between real and financial assets. Financial assets are related to the future ability of issuers to generate cash flows for dividends […]

Fisher on Debt – It is a Cycle and When Optimism Falls, So Will Financial Assets

…the public psychology of going into debt for gain passes through several more or less distinct phases:

(a) the lure of big prospective dividends or gains in income in the remote future;

(b) the hope of selling at a profit, and realizing a capital gain in the immediate future;

(c) the vogue of reckless promotions, taking advantage of the habituation of the public to create expectations;

(d) the development of downright fraud, imposing on a public which has grown credulous and gullible.

“The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions” Irving Fisher

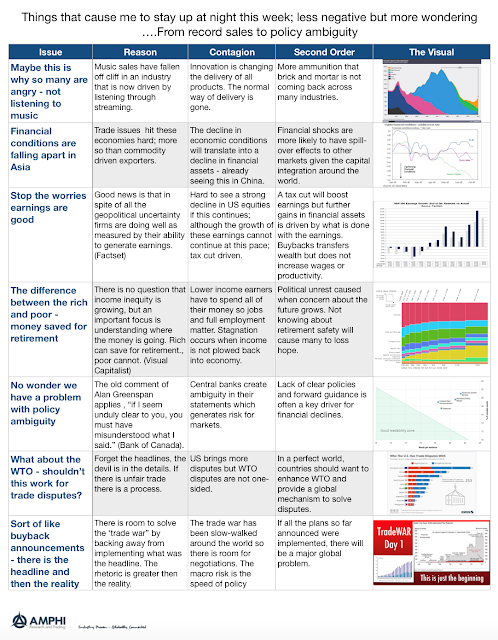

Things That Make Me Stay Up At Night This Weekend – From Music to Ambiguity

I have fewer concerns this week; however, there is significant risk with inflation. Inflation is growing around the world. We are pass 2% in the US by any number of measures. Let the overshoot begin. There is little reason so see the Fed changing their behavior and there is a stronger case for further money reduction around the world. The trade rhetoric is still high and there is general agreement that further trade action will slow growth, yet we continue to move down this path.

The Relationship Between Financial or Real Assets is at Extremes – It Can Be Exploited

Correlation is not causality. Blending two variables on the same graph does not make a relationship, but there is a core link with the relationship between real and financial assets. Financial assets are related to the future ability of issuers to generate cash flows for dividends or for paying down debt. Growth in real assets are linked to the demand for resources to sustain current and future consumption.

Technical and Practical Knowledge – You Need Both for Asset Management

Can anyone who has technical knowledge become a good money manager? This is a fundamental question for the quant revolution.